CREATE TABLE table_name (

column1 INTEGER,

column2 TEXT,

column3 INTEGER

);The SQL Is Never As Good As The Original

SQL is a popular way of working with data. Advanced users probably do a lot with it alone, but even just having a working knowledge of SQL has increased the number of datasets that I can get data from to then analyse with other tools such as R or Python. You can use SQL within RStudio if you want. The following are a few notes to help future-Rohan when he needs to use SQL. A worked example with a sample of the Hansard data will be included in a future post.

Thanks to Monica for the title.

Introduction

SQL is a popular way of working with data. Advanced users probably do a lot with it alone, but even just having a working knowledge of SQL has increased the number of datasets that I can get data from to then analyse with other tools such as R or Python. You can use SQL within RStudio if you want. The following are a few notes to help future-Rohan when he needs to use SQL. A worked example with a sample of the Hansard data will be included in a future post.

SQL is fairly straightforward if you’ve used mutate, filter and join in the R tidyverse as the concepts (and sometimes even the verb) are the same. In that case, half the battle is getting used to the terminology, and the other half is getting on top of the order of operations because SQL can be a tad pedantic.

SQL (“see-quell” or “S.Q.L.” - both camps seem fairly insistent on their way…) is used with relational databases. A relational database is just a collection of at least one table, and a table is just some data organized into rows and columns. If there’s more than one table in the database, then there should be some column that links them. Using it feels a bit like HTML/CSS in terms of being halfway between markup and programming. One fun aspect is that line spaces mean nothing: include them or don’t, but always end a SQL command in a semicolon;

Creating a table

Create an empty table of three columns of type: int, text, int:

Add a row of data:

INSERT INTO table_name (column1, column2, column3)

VALUES (1234, 'Gough Menzies', 32);Add a column:

ALTER TABLE table_name

ADD COLUMN column4 TEXT;Viewing the data

See one column (similar to R’s select):

SELECT column2

FROM table_name;See two columns:

SELECT column1, column2

FROM table_name;See all columns:

SELECT *

FROM table_name;See unique rows in a column (similar to R’s distinct):

SELECT DISTINCT column2

FROM table_name;See the rows that match a criteria (similar idea to R’s which or filter):

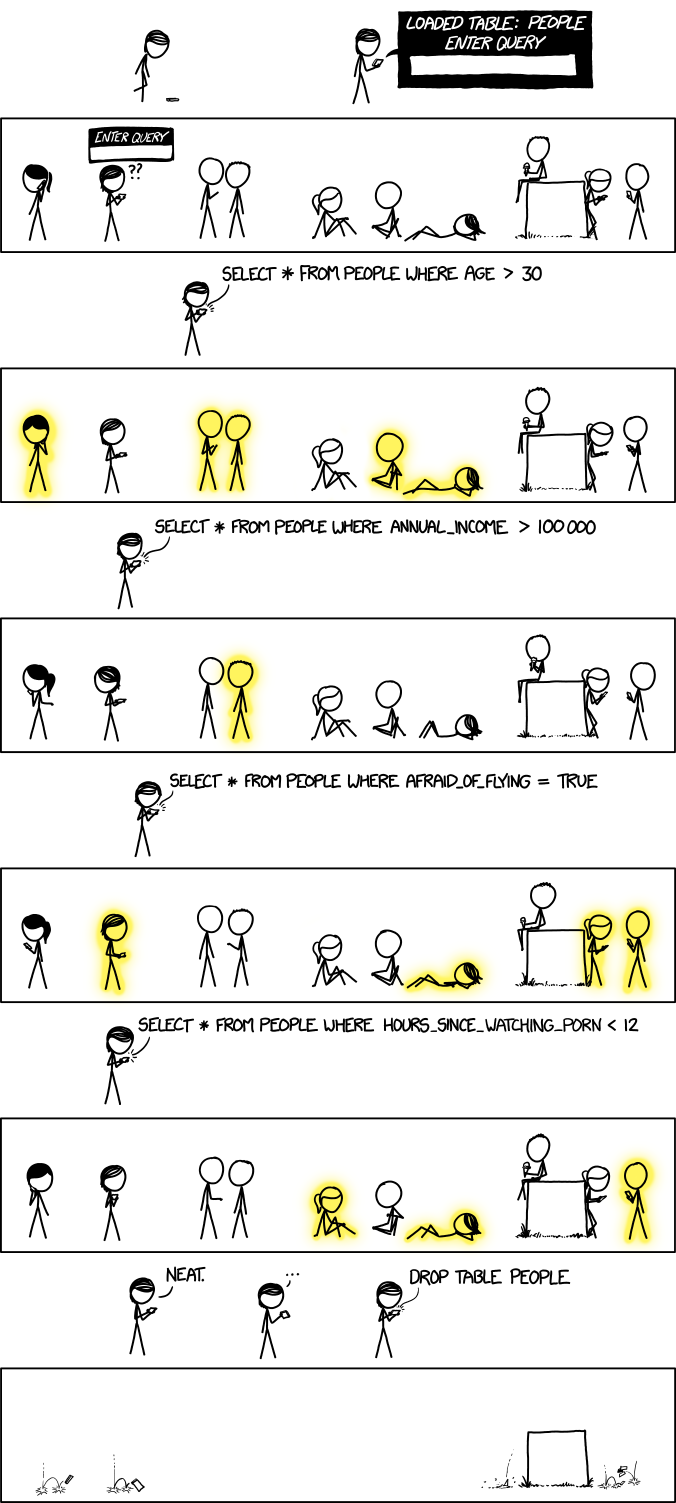

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column3 > 30;All the usual operators are fine with WHERE: =, !=, >, <, >=, <=. Just make sure the condition evaluates to true/false.

See the rows that are pretty close to a criteria:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column2 LIKE '_ough Menzies';The _ above is a wildcard that matches to any character e.g. ‘Cough Menzies’ would be matched here, as would ‘Gough Menzies’. LIKE is not case-sensitive: ‘Gough Menzies’ and ‘gough menzies’ would both match here.

Use % as an anchor to matches pieces:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column2 LIKE '%Menzies';That matches anything ending with ‘Menzies’, so ‘Cough Menzies’, ‘Gough Menzies’, ‘Sir Menzies’ etc, would all be matched here. Use surrounding percentages to match within, e.g. %Menzies% would also match ‘Sir Menzies Jr’ whereas %Menzies would not.

This is wild: NULL values (!) (True/False/NULL) are possible, not just True/False, but they need to be explicitly matched for:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column2 IS NOT NULL;This too is wild: There’s an underlying ordering build into number, date and text fields that allows you to use BETWEEN on all those, not just numeric! The following looks for text that starts with a letter between A and M (not including M) so would match ‘Gough Menzies’, but not ‘Sir Gough Menzies’!

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column2 BETWEEN 'A' AND 'M';If you look for a numeric (as opposed to text) then BETWEEN is inclusive.

Combine conditions with AND (both must be true to be returned) or OR (at least one must be true):

SELECT *

FROM table_name

WHERE column2 BETWEEN 'A' AND 'M'

AND column3 = 32;You can order the result:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

ORDER BY column3;Ascending is the default, add DESC for alternative:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

ORDER BY column3 DESC;Restrict the return to a certain number of values by adding LIMIT at the end:

SELECT *

FROM table_name

ORDER BY column3 DESC

LIMIT 1;(This doesn’t work all the time - only certain SQL databases.)

Modifying data and using logic

Edit a value:

UPDATE table_name

SET column3 = 33

WHERE column1 = 1234;Implement if/else logic:

SELECT *,

CASE

WHEN column2 = 'Gough Whitlam' THEN 'Labor'

WHEN column2 = 'Robert Menzies' THEN 'Liberal'

ELSE 'Who knows'

END AS 'Party'

FROM table_name;This returns a column called ‘Party’ that looks at the name of the person to return a party.

Delete some rows:

DELETE FROM table_name

WHERE column3 IS NULL;Add an alias to a column name (this just shows in the output):

SELECT column2 AS 'Names'

FROM table_name;Summarising data

We can use COUNT, SUM, MAX, MIN, AVG and ROUND in the place of summarise in R. COUNT counts the number of rows that are not empty for some column by passing the column name, or for all using *:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM table_name;Similarly, pass a column to SUM, MAX, MIN, and AVG:

SELECT SUM(column1)

FROM table_name;ROUND takes a column and an integer to specify how many decimal places:

SELECT ROUND(column1, 0)

FROM table_name;SELECT and GROUP BY is similar to group_by in R:

SELECT column3, COUNT(*)

FROM table_name

GROUP BY column3;You can GROUP BY column number instead of name e.g. 1 instead of column3 in the GROUP BY line or 2 instead of COUNT(*) if that was of interest.

HAVING for aggregates, is similar to filter in R or the WHERE for rows from earlier. Use it after GROUP BY and before ORDER BY and LIMIT.

Combining data

Combine two tables using JOIN or LEFT JOIN:

SELECT *

FROM table1_name

JOIN table2_name

ON table1_name.colum1 = table2_name.column1;Be careful to specify the matching columns using dot notation. Primary key columns uniquely identify rows and are: 1) never NULL; 2) unique; 3) only one column per table. A primary key can be primary in one table and foreign in another. Unique columns have a different value for every row and there can be many in one table.

UNION is the equivalent of cbind if the tables are already fairly similar.